Development of the Arthurian Legend

One day, long before the idea for The Swithen series was formed or any of the books written, I had the impulse to find out the real story of King Arthur. I found Le Morte D’Arthur and began reading, soon discovering that what’s there is far from a cohesive, linear story.

A little more research revealed that what we call the Arthurian Legend is actually a compilation of several different stories conceived at different times by different authors for different purposes, all loosely stitched together.

What that means is: There is no one, correct story of King Arthur.

This is a crucial understanding for anyone beginning to delve into the Arthurian legend. What it means is there is no definitive version of the story, and more importantly, no “right” version of the story. There are only more and less popular tellings, and tellings that have endured through time better than others. That said, the legend came to a major milestone with the publication of Le Morte D’Arthur in 1485, so we can use that as the endpoint of the Medieval development of the story.

Now let’s take a look at how this legend came down to us through time.

The earliest beginnings

Arthur first appears in historical records in two chronicles, although the actual historical accuracy of these chronicles is uncertain. They are the Historia Brittonum (History of the Britons) and Annales Cambriae (Welsh Annals). These were written in the 9thcentury, but describe events taking place in the 5thand early 6thcentury.

These chronicles say that Arthur was a great leader who fought in twelve battles against the invading Saxons, the last being the battle of Camlann, where he was killed by Mordred. At this point it does not identify Mordred as Arthur’s son or even say that they killed each other.

At the same time Arthur appears in several Celtic legends, fighting enemies both human and supernatural. He appears in the tales collected in The Mabinogion, the poems of Taliesin, the Welsh Triads and various saints’ lives.

Early elements of the saga:

- Arthur

- Mordred

- Guinevere

- Saxons

- Arthur’s twelve battles

The first narrative

In 1136, Geoffery of Monmouth released his History of the Kings of Britain, which follows the development of Britain from the legendary Trojan exile Brutus to the 7th-century Welsh king Cadwallader (and also includes the inspiration for Shakespeare’s King Lear). It is largely considered to be complete fiction, made up by Geoffery. This was the first extensive narrative of Arthur’s story, taking the saga from Vortigern through Pendragon/Aurelius and Uther to the birth of Arthur. It includes his twelve battles and his death at Camlann, but adds several new things.

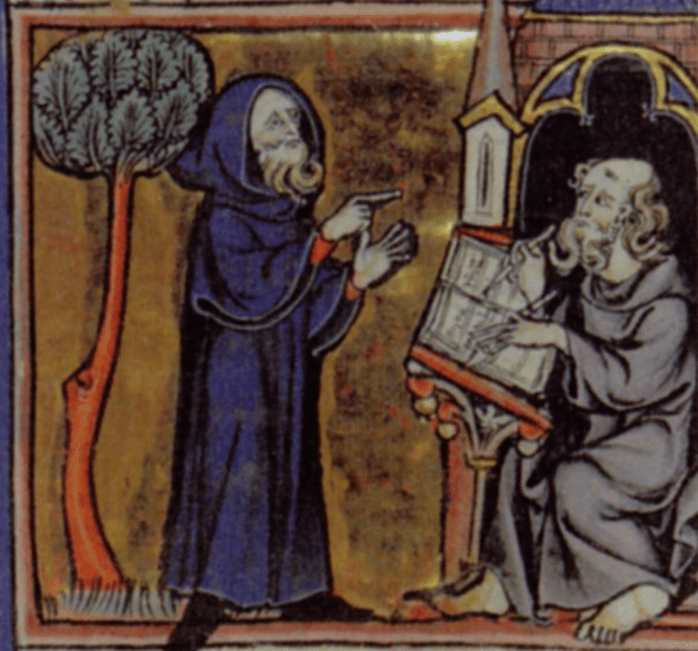

Geoffery was hugely influential in setting elements of the story that would endure to this day. He introduced Merlin into the Arthur story, eschewing the traditional rendering of Merlin as a wild man of the woods and embracing the origin story that he is the son of an incubus and a human woman. Merlin helps Arthur with his initial battles, then vanishes from the tale.

Geoffery also introduces the characters of Kay, Bedivere, Gawain. He added the twist that Mordred kidnaps Guinevere and attempts to take over Arthur’s kingdom (although Mordred is still not Arthur’s son). He added the challenge that Rome makes to Arthur’s rule, the battle with the giant of St. Michael’s mount, and the island of Avalon. His work was then further developed by Wace and Layamon.

What Geoffery and followers add to the saga:

- Arthur’s predecessors, Vortigern, Pendragon/Aurelius and Uther

- The story of Arthur’s birth and mother, Igraine

- Merlin’s assistance to Arthur’s early reign

- Kay, Bedivere, Gawain

- Challenge from Rome and giant of St. Michael’s Mount

- Mordred’s kidnapping Guinevere and usurping the throne

- Avalon

- The Round Table (added by Wace)

Transformation into romance

Between the years of 1170 and 1190, French writer Chrétien de Troyes wrote a number of short prose romances that proved to be tremendously influential on the development of the legend. Their most prominent feature is the addition of the character Lancelot, and the idea that Lancelot is carrying on an affair with Guinevere. These romances are also where Arthur starts to be pushed into the background, his knights instead taking center stage in the story.

Chrétien’s other major addition was the character of Percival and the addition of the Holy Grail, although the grail is just seen and mentioned, there is not yet any quest for it. He also provides the first mention of Camelot, although only in passing.

What Chrétien de Troyes adds to the saga:

- Lancelot

- Lancelot’s affair with Guinevere

- Serious elevation of the role of chivalry

- Percival

- The Fisher King

- The Holy Grail (but not the quest for it)

- Camelot

The main storylines are joined

Now we get to the longest and most complete version of the legend, the Vulgate Cycle, composed between 1215 and 1230. This version began with the six-part Lancelot, a significant expansion of the character invented by Chrétien de Troyes. In this version, Lancelot is abducted by Nimue, the Lady of the Lake, and grows up in her underwater realm alongside Bors and Lionel. This version significantly expounds on Lancelot’s psychology and even includes a male love interest for him, Galehaut, who was dropped from the story going forward.

The Vulgate has the first inclusion of the quest for the Holy Grail, the introduction of Galahad, as well as a detailed version of Arthur’s decline and eventual death. After the Lancelot sections were complete, the beginning of the story was added, one tracing the story of the Holy Grail from just after the crucifixion up to Merlin’s time. It also incorporates and fleshes out the story of Merlin, Arthur’s birth, ascension, and first battles.

Now what happens here, however, is that the story is reworked into an explicitly Christian narrative. Merlin is now the son of the devil created in revenge for Christ’s hallowing of hell, the Holy Grail is now officially the cup used to collect Christ’s blood, and the story culminates in the quest for the Holy Grail, in which the Knights of the Round Table learn that, after all that wanton killing, they are not worthy Christians at all—including Lancelot, whose love of Guinevere renders him ineligible for redemption.

The Post-Vulgate cycle rewrites the story without Lancelot, adding a new version of the quest for the grail, the death of Arthur and the story of Merlin. It adds the characters of Balin and Balan, and Morgan le Fay’s attempt to place her lover Accolon on the throne, both so indelible from later versions.

What the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate Cycles add to the saga:

- Lancelot’s nephews Bors and Lionel

- That Lancelot was kidnapped and raised by the Lady of the Lake

- Galahad

- The Holy Grail as Christian artifact

- The quest for the Holy Grail

- Merlin’s origin as the son of the devil

- Arthur’s downfall as a result of Lancelot and Guinevere’s affair

- Balin and Balan

- Morgan le Fay’s attempt to place Accolon on the throne

Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur

Fast-forward to around 1485, when Sir Thomas Malory is in prison. He undertakes—perhaps to pass the time—to arrange and combine his selection of the Arthurian stories into one semi-cohesive saga, the only one composed by a single author, and short enough to be accessible to readers.

Malory made his own changes to the legend, which are important to consider as well. First, in shortening the saga, he left out several key stories, some of which are mind-boggling omissions—like Merlin’s origins or Lancelot’s parentage, both of which throw Arthur’s story into an entirely new light. He also arranged the stories into his own order, which implies a sequential occurrence they did not originally have. Finally, he ruthlessly edited the stories down to their bare bones, which can be so economical and focused on actions they can be difficult to understand, and difficult to pull meaning and depth from. Malory’s hand can be felt throughout the entire work, and another whole area of study is what he added, omitted and emphasized.

This happened to coincide with the development of the printing press, making Le Morte D’Arthur one of the earliest printed books in England. It became a runaway success and as a result, is considered by many to be the definitive telling of the Arthurian legend. Almost all Arthurian works that followed derive in some way from Le Morte D’Arthur.

What Malory added:

What came to be known as the definitive shape and order of the entire saga

What does The Swithen do?

Now, I don’t imagine that my interpretation advances the Arthurian legend in any way, but now that you have an appreciation for how this legend was formed over the years, you are in a better place to understand my intentions with The Swithen book series:

- Present a fuller adaptation bringing back many of the parts Malory dropped, some of which have important implications for the overall saga.

- Further unify the story into one cohesive whole where all the parts work together.

- Develop characters and add plausible psychologies to help us understand the characters as human beings.

- Flesh out the past for each character. In the legend we hear of several events that occurred in the past. In my series we see them happen so we can follow a character’s development.

- Make relationships clear. It adds a potent layer of meaning to understand interconnected relationships of each character, which can be obscure in the sources.