Who is Merlin? His Legendary Origins

The most famous and well-known wizard ever, Merlin has been the inspiration for every single wizard to follow, from Gandalf in Lord of the Rings to Dumbledore of Harry Potter—even Yoda from Star Wars. Pretty much every wizard figure who exists in any form since 1500 owes his inspiration to Merlin. But what are the real literary origins of Merlin, and what is his real story? Let’s break that down here.

The earliest origins: Myrddin Wyllt

The figure who came to be known as Merlin first appeared in Welsh mythology prior to the 1100s, where he was known as Myrddin Wyllt. The name Myrddin is thought by some to be a combination of “Mer” (mad) and the Welsh word “Dyn” to mean “madman.” He was portrayed as a bard driven mad by the horrors of war who then fled to live in the Caledonian wood. He lives in the wilderness, wanders in the company of animals, and has some prophetic qualities.

Legendary figures combine

Other figures from legend were incorporated by Geoffery of Monmouth when he produced his first work containing Merlin, the Prophetiae Merlini (“Prophecies of Merlin” of 1130). He combined Emrys, a character partly based on 5th-century historical figure Ambrosius Aurelianus. The prophecies claim to be the words of the seer and make several claims of the future, but reveal no information about his character or past.

When Geoffery portrayed Merlin into his most famous work, the Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) of 1136, he incorporated stories by 9thcentury writer Nennius about Ambrosius is discovered by Vortigern, who wished to build a tower that kept collapsing before completion. Wise men advised him that the foundation must be sprinkled with the blood of a fatherless boy, which was Ambrosius. Note that he is just said to be fatherless at this point, not that his father was a demon. When Ambrosius is brought to the king, he says that beneath the fountain is a lake containing two dragons, a white one representing the invading Saxons, and a red one representing the native Celtic Britons. That red dragon is still on the Welsh flag to this day. This story, as well as the battle of the two dragons, is told in The Sons of Constance,The Swithen Book Two.

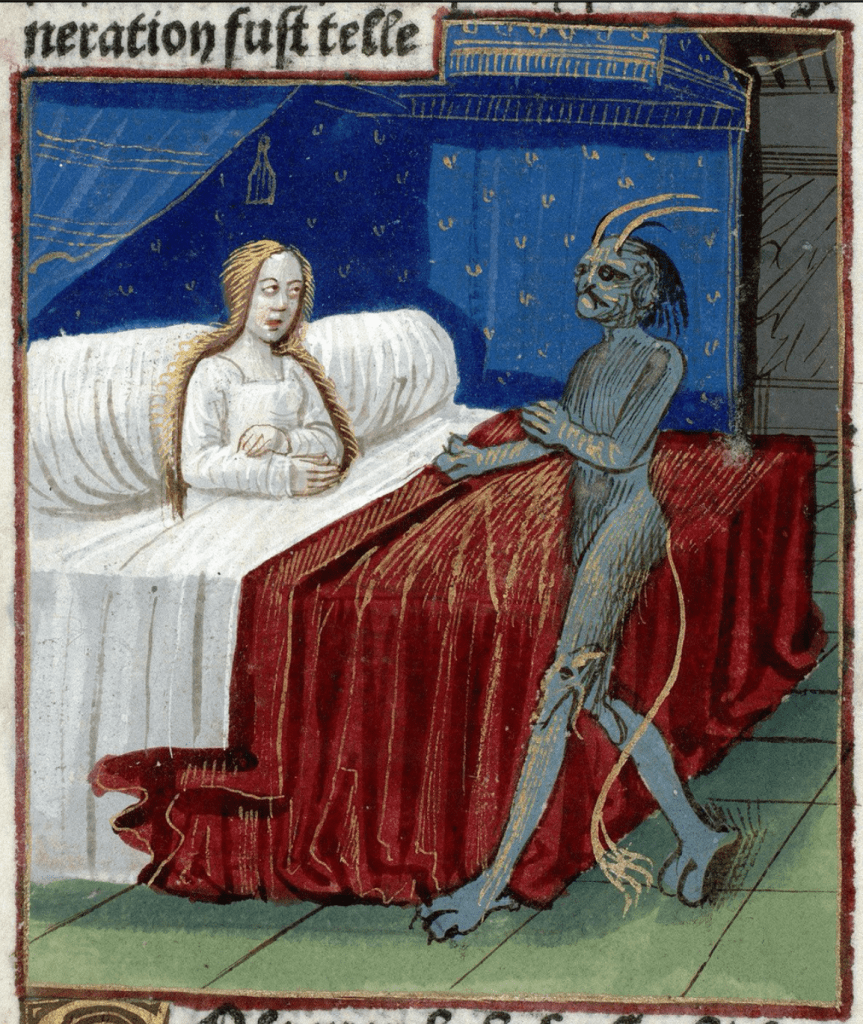

Merlin as the son of a demon

Geoffery was the first to intertwine Merlin with King Arthur, in the History of the Kings of Britain of 1136. This is the first to say that Merlin was fathered by a demon on a human woman and becomes involved with Vortigern when brought in to advise on his tower. Usually the woman is not named, leading me to invent the name Meylinde in the first versions of the opening novel of my series. Later learning that she is named Adhan (pronounced ah-dhan) in the oldest version of the Prose Brut of approximately 1272, I updated the name in order to adhere to my own principles of being as faithful as possible to the early Arthurian sources. Merlin is said to be born very hairy and able to speak like an adult, as well as possessing supernatural knowledge that he uses to save his mother when she is brought to trial for bearing an illegitimate child. The story of Merlin’s birth and his mother’s trial is told in A Man of Our Kind: The Swithen Book One.

Merlin meets King Arthur

So what’s missing from all this so far? King Arthur! Geoffery followed the story of Vortigern with the older son of the king Vortigern had murdered in order to take the throne, then called Aurelius Ambrosius, later known as Pendragon (as he is in The Swithen). His younger brother is Uther. Now this is where Geoffery begins inventing his own stories (or at least no one knows the sources he used). In this version, Merlin makes Stonehenge as a tomb for Aurelius, then helps new king Uther change his appearance in order to enter Tintagel and sleep with Igerna (Igraine), conceiving of Arthur. But it this version Merlin disappears, not hanging around to help Arthur as he does in later versions.

The Merlin we have come to know

Merlin first started taking on his most established origin story in Robert de Boron’s Old French epic poem Merlin, which first established his ability to shape-shift and explicitly made him the son of the Christian devil, created in response to Christ’s redeeming of all the souls confined to hell before His coming. This version adds the character of Blaise, who has the idea to free Merlin from the devil’s influence by having him baptized immediately after birth. In this version, the devil grants Merlin knowledge of the past in order to tempt people into damnation, and after birth God grants him knowledge of the future and the freedom to choose his own path.

The poem then goes on to supply many of the elements we know from the familiar tale, such as Merlin creating the Round Table for Uther and Arthur pulling the sword from the stone. These tales were incorporated into the Vulgate Cycle, which was used as a primary source for Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur, which became the classic version of the Arthurian legend—and thus, the iconic version of Merlin—for the vast majority of people.

Merlin in The Swithen

Since what we know as the Arthurian legend is actually a compilation of several different legends created by different parties across about 500 years, there is not always a great deal of cohesion to the many different versions of the story. For this reason, even the versions that begin with Merlin as the son of the devil then drop this entire angle and never again consider the consequences of it. Merlin was redeemed through baptism and that is simply the end of the matter.

When I was first researching the numerous versions of the legend, I was in shock that such a monumental storyline could be simply dropped, not to mention the lore-shattering revelation that, if you accept the addition of Merlin’s demonic origin, the entire story of King Arthur was the result of a failed takeover attempt by the Christian devil. The answer is that the King Arthur story was conceived long before the Merlin-as-devil’s-son story was added to the beginning, and the later story never adjusted. But if I am writing a cohesive version that attempts to unify all the strands, how should I handle that?

I decided I could not pretend that Merlin’s origin as the devil’s son could not just be ignored. Thus, in The Swithen novels, Merlin begins as a redeemed devil keen on pleasing God by spreading Christianity, and gradually develops toward the more agnostic version most of us are familiar with.

The other thing I had to face down is that Merlin the kindly old wizard who is never wrong is not exactly the most interesting character and also has no room for development. He is perfect as he is. Thus I leaned hard into the things we do know about the character, one of which is that he is born with all knowledge of the past and future but without any life experience, and for that reason, in my novels, Merlin lacks emotional intelligence and has to learn it. Because he sees across history, he has trouble seeing individuals and appreciating their struggles, which will become a serious issue when he has to wrangle the strong-willed Arthur. All of this provides him with a character arc so he can develop as we go through the novels and have more depth than the bland, all-knowing perfect being we are familiar with.

As with everything about the Arthurian legend, there is no one cohesive story, and no one, definitive Merlin. But as anyone can see from even our most current popular culture, the figure of Merlin casts an irresistible spell that remains as enchanting as ever.